1 Intro

This post is a walkthrough on writing a Mesop app. We will be building a Jeopardy game that uses Gemini to verify the correctness of user responses. The UI is of moderate complexity and illustrates various aspects of working with Mesop.

2 Why Jeopardy?

At my previous job, I maintained a Jeopardy Slack bot that posted random questions every couple hours during the work week. An hour later it would post the answer. The delay was a nice way because it helped generate some occasionally fun non-work discussion.

One feature, I always wanted to add was the ability to verify people’s answers on the fly. Back then, it wasn’t possible due to the freeform nature of the responses. So when ChatGPT 3.5 came out, it occurred to me that LLMs could handle this use case easily. The J-Archive was probably ingested as part of the training data as well.

I never got the chance to implement this since I moved to a new job. So for this Mesop app, I thought it’d be fun to build out a Jeopardy app with LLM integration.

3 Why Mesop?

I started contributing to Mesop earlier this year. It’s a relatively new framework, so I thought it’d be nice to dogfood the framework see what’s working and what’s not working. Plus, there are no detailed tutorials on Mesop yet.

4 What is Mesop?

Mesop is a Python UI framework that reduces the complexity of writing interactive web applications. It does this by abstracting out the frontend. Mesop uses Angular behind the scenes. The user does not need to know how to set up an Angular app. Nor do they need to know how to connect Angular to a backend server. All they need to know is Mesop.

CSS/HTML knowledge is still required to a certain extent (especially CSS), but it’s not a hard requirement to using Mesop. Rudimentary knowledge can get people pretty far.

At the moment, I’d say Mesop is geared toward building out fast prototypes, especially ML related demos. AI/ML engineers likely won’t have strong expertise in frontend development, but they will be familiar with Python. In this regard, Mesop fills a similar niche as Gradio and Streamlit, both of which are very popular and established frameworks.

I can also envision a future where Mesop can be used for building performant, secure, and production-ready web applications. So in this way, Mesop has some similar use cases to HTMX and FastUI.

5 Running the app

Before walking through the Mesop Jeopardy app, it may be helpful to run the app.

You will need a Google API Key for Gemini Pro. You can create one using the instructions at https://ai.google.dev/gemini-api/docs/api-key.

git clone git@github.com:richard-to/mesop-jeopardy.git

cd mesop-jeopardy

pip install -r requirements.txt

GOOGLE_API_KEY=<your-api-key> mesop app.py

You should now be able to view the app at localhost:32123

6 Walkthrough

This section contains a walkthrough of the Mesop Jeopardy app.

6.1 State

Mesop apps manage the UI state using a specialized dataclass. The state object maintains the state of the application between browswer requests.

Here is what the Jeopardy app state class looks like:

@me.stateclass

class State:

selected_clue: str

# We use a dict since dataclasses do not seem to be deserialized back to a dict.

# This may be due to the use of the nested list.

board: list[list[dict[str, str | int]]] = field(

default_factory=lambda: make_default_board(_JEOPARDY_QUESTIONS)

)

# Used for clearing the text input.

response_value: str

response: str

answer_is_correct: bool = False

answer_check_response: str

score: int

# Key format: click-{row_index}-{col_index}

selected_question_key: str

# Set is not JSON serializable

# Key format: click-{row_index}-{col_index}

answered_questions: dict[str, bool]

modal_open: bool = False

6.1.1 Common uses cases / gotchas / workarounds

The state object is integral to Mesop apps since it’s needed to provide interactivity. This section includes some helpful tips for using state.

Storing the value of inputs

If you have a text input, we need a way to capture the user’s input so we can use it to perform calculations or display it elsewhere.

In the Jeopardy app, we store the user’s input with the response field.

Storing the state of a UI element

A common use case is a modal component. We need to store a boolean to keep track of whether the modal is visible or not.

Here, we store the user’s input with the modal_open field.

Clearing user input

In Mesop, this is slightly unintuitive. This should be easier or more natural to do since it is a common use case.

In order to clear a text input, you need a second state field. Here, we use a field

called response_value.

Notice how we set state.response_value to the value parameter. This value

parameter stores the “initial” value of the textarea.

me.textarea(

label="Enter your response",

value=state.response_value,

disabled=not bool(state.selected_question_key),

on_input=on_input_response,

style=css.RESPONSE_INPUT,

)

It’s important to know that this does not capture the user’s input. That can done using

an on_input event handler.

def on_input_response(e: me.InputEvent):

"""Stores user input into state, so we can process their response."""

state = me.state(State)

state.response = e.value

If you update the value parameter, this will overwrite the user input. So to reset

the textarea, you can update the response_value state.

The caveat is that Angular won’t know to reset the value unless you change the

response_value. This triggers a diff in the component on the Angular side.

def on_click_submit(e: me.ClickEvent):

# Other logic here

# Hack to reset text input. Update the initial response value to current response

# first, which will trigger a diff when we set the initial response back to empty

# string.

#

# A small delay is also needed because some times the yield happens too fast, which

# does not allow the UI on the client to update properly.

state.response_value = state.response

yield

time.sleep(0.5)

state.response_value = ""

yield

Initializing non-primitive defaults

The thing to remember is that the state object is essentially a dataclass with some

Mesop specific functionality. This means you can set defaults using the

dataclasses.field function with a default_factory.

@me.stateclass

class State:

board: list[list[dict[str, str | int]]] = field(

default_factory=lambda: make_default_board(_JEOPARDY_QUESTIONS)

)

Serialization / Deserialization

The Mesop state class is serialized / deserialized into JSON and back. The state is passed back and forth on each request since Mesop apps do not save state on the server.

It is easy to run into serialization issues if you use objects that are not JSON serializable. Mesop does not include a way to add custom serialization rules, so in it is safer to use primitives.

Dataclasses can be serialized. But there are cases where deserialization will return a dict rather than the dataclass.

This issue occurred in the Jeopardy app, perhaps because of the nested list usage here. This is why we had to store the clues as dicts.

@me.stateclass

class State:

board: list[list[dict[str, str | int]]] = field(

default_factory=lambda: make_default_board(_JEOPARDY_QUESTIONS)

)

6.2 Styles

Mesop does not support CSS. Instead styles are applied inline. The nice thing about this is users do not need to think much about how CSS rules cascade. There are cases where the inline styles do cascade a bit, such as setting the font size on a box component will also affect the font size in a nested text component.

Mesop does not support all CSS properties. Only a subset of common properties are exposed. We’ve been adding new properties as a needed.

There are downsides to using inline styles, such as not being able to use media queries for responsive designs. Also pseudo-classes and psuedo-elements are not supported when using inline styles.

Another downside is that there is no compatibility with external CSS Frameworks, such as Bootstrap or Tailwind. This, however, does not prevent someone from creating a CSS framework for Mesop that provides similar functionality. It just won’t be part of the core framework.

From a developer experience standpoint, styling Mesop apps could be a bit better. Although the styles can be added directly to the components, this often adds a lot of clutter to the code, so I tend to separate out the styles into a separate file. This is not ideal since I have to keep going back and forth to check the styles. In this way it is reminiscent of using a simplified style sheet.

Usage of the Style class is relatively straightforward, so no example is necessary

here.

One nice thing about using inline styles that I’d like to highlight, is that the individual style properties can be modified easily, especially in response to user interactions.

For example, I have a function that generates a Style for the clue box based on

whether it is selectable or not. If it is selectable, we will change the cursor to

pointer, otherwise, we use the default.

def clue_box(is_selectable: bool) -> me.Style:

"""Style for clue box

Args:

is_selectable: Visual signify if the clue is selectable.

"""

return me.Style(

background=COLOR_BLUE,

color=COLOR_YELLOW,

cursor="pointer" if is_selectable else "default",

font_size="1em",

font_weight="bold",

padding=me.Padding.all(15),

text_align="center"

)

6.3 Layout

Writing the layout for a Mesop is very intuitive. I like that it invites mixing logic with the UI and even CSS. In the early days of writing web apps, there was a strict adherence to separating presentation, layout, and data/logic. But ever since React, I feel like mixing everything together is much more acceptable.

Mesop apps are mainly a bunch of box components with some styles applied. Then the rest are common components, such as buttons, inputs, text, and images.

Here is an example of generating the Jeopardy grid:

with me.box(style=css.MAIN_COL_GRID):

with me.box(style=css.BOARD_COL_GRID):

for col_index in range(len(state.board[0])):

# Render Jeopardy categories

if col_index == 0:

for row_index in range(len(state.board)):

cell = state.board[row_index][col_index]

with me.box(style=css.CATEGORY_BOX):

me.text(cell["category"])

# Render Jeopardy questions

for row_index in range(len(state.board)):

cell = state.board[row_index][col_index]

key = f"clue-{row_index}-{col_index}"

is_selectable = not (key in state.answered_questions or state.selected_question_key)

with me.box(style=css.clue_box(is_selectable), key=key, on_click=on_click_cell):

if key in state.answered_questions:

me.text("")

elif key == state.selected_question_key:

me.text(cell["question"], style=me.Style(text_align="left"))

else:

me.text(f"${cell["normalized_value"]}", style=me.Style(font_size="2.2vw"))

We are able to render our layout using regular Python. No need for a templating language, such as Jinja.

This nice because we can write Python loops to dynamically generate the board. There are loops in Jinja as well, but it’s one less thing to learn, one less file to create. And personally, it feels slightly less clunky than using a templating language.

And from a readability standpoint, it’s easy enough to read since everything is bundled together.

6.3.1 How does it work?

I’m not expert at the internals of Mesop, but at a high level, what happens is the Python code is converted into a component tree using protobuffs. This component tree is sent to the client to be rendered by Angular.

You may be wondering if sending the component tree back and forth on each request is inefficient. That occurred to me as well. It reminded me of the old “view state” feature from old ASP.NET web apps. If done incorrectly, this led to the very large view states for relatively simple applications.

We’re still working on making performance improvements to Mesop, but one improvement we implemented recently is returning a diff of the component tree rather than the whole tree. Typically, only a small portion of the UI will change after a user interaction.

6.4 Event Handlers

Mesop’s event handlers allow for user interaction. Essentially client side events are proxied to the server side. The logic is applied; the state and UI is updated; and the updates are sent back to the server.

There are downsides to this approach, since latency becomes a potential issue. For example events, such as mouseovers and key press events could fire quite frequently, and is not that feasible to keep sending those events to the server. One option is to bundle the events together before sending them to the server, but that behavior would not be the same as the client-side behavior.

For common cases, such as input, click, and change events, they fire infrequently enough, that sending the event back to the server for processing is OK.

6.4.1 A simple example

Consider a text input or text area. The typical pattern is to add an on_input event

handler. Then just store the value of the input into the field in the state class. This

allows you to reference the input later when the user submits the form or what not.

For other events, such as sliders, checkboxes, and radios, you’d do some thing similar. You’d just use their respective event handlers.

def on_input_response(e: me.InputEvent):

"""Stores user input into state, so we can process their response."""

state = me.state(State)

state.response = e.value

6.4.2 Reusing event handlers

In Javascript, you can reuse functions for event handlers by using anonymous or arrow functions. This allows you to pass in different arguments but still use the same function.

In Mesop, this is not possible. Use of lambdas, decorated functions, nested functions, partial functions (via functools) will not work.

For more information, see https://google.github.io/mesop/guides/troubleshooting/#avoid-using-closure-variables-in-event-handler

The workaround is to use the key argument that is associated with each Mesop

component.

A good example of this usage is rendering the Jeopardy board. Each cell needs to be clickable. In addition, the cells are generated dynamically. It would not make sense to have to hardcode a function for each cell.

We use the key argument to store the row and column index. The event handler object

will contain this key. We could then parse the key and use then determine the clicked

cell.

def on_click_cell(e: me.ClickEvent):

"""Selects the given clue.

This function is noop if the following states are true:

- Clue is already selected (user must answer first).

- Clue is alreaady answered (can't answer clues that have already been done).

"""

state = me.state(State)

if state.selected_question_key or e.key in state.answered_questions:

return

state.selected_question_key = e.key

For the Jeopardy app, we store the key in the state class and parse it later using the get_selected_question helper function.

def get_selected_question(board, selected_question_key) -> dict[str, str]:

"""Gets the selected question from the key."""

_, row, col = selected_question_key.split("-")

return board[int(row)][int(col)]

6.4.3 Event handler yielding

One interesting aspect of how event handlers work is that you can yield multiple times.

On each yield, the updated component state is sent to the client. This allows you to do some timed behaviors, such as flash messages that you want to show briefly. If you have a long operation, you can render a loading icon, then hide it later.

This example was showed earlier, but showing it again since it’s the only example

of using yield in an event handler in the Jeopardy app.

def on_click_submit(e: me.ClickEvent):

# Other logic redacted.

# Hack to reset text input. Update the initial response value to current response

# first, which will trigger a diff when we set the initial response back to empty

# string.

#

# A small delay is also needed because some times the yield happens too fast, which

# does not allow the UI on the client to update properly.

state.response_value = state.response

yield

time.sleep(0.5)

state.response_value = ""

yield

6.5 The Jeopardy questions

This part is not Mesop specific. It is just basic data clean up and formatting.

The most important part about Jeopardy is the questions. We need questions to display on the board. I use an old dataset I found awhile ago on Reddit. It’s a dataset containing 200K questions from the start of Jeopardy all the way to about 2010 or so. I believe the questions were scraped from the J Archive, so I don’t want to include the dataset in the repo. It’s easy to find.

You could also update the code to use an LLM to generate questions in the expected format. I like using the actual questions since, the real questions can be a lot of fun. Though I think an LLM could generate similar fun questions if given specific categories and instructions. The LLM would just need to generate a JSON list of questions in this format:

{

"category": "HISTORY",

"air_date": "2004-12-31",

"question": "'For the last 8 years of his life, Galileo was...",

"value": "$200",

"answer": "Copernicus",

"round": "Jeopardy!",

"show_number": "4680"

}

Having worked with this dataset before I was familiar with its various quirks:

- Single quotes are around each question for some reason

- There is some HTML that needs to be stripped

- There are images / and audio links for visual/auditory clues

- Final Jeopardy questions have no value associated with them

- Daily Doubles have the wagered value instead of the actual value on the board

- The dollar values changed changed at some point. In addition the Double Jeopardy! rounds also has different values from the Jeopardy! rounds.

One thing I wanted to do is render question sets by category, but have the ability to randomly mix and match them rather than just render the questions grouped by show.

Because of this requirement, the dollar values would be all over the place. For example we could have a mix of question sets from the early 80’s, mid-90’s, Jeopardy!, Double Jeopardy!. There are also Daily Double questions.

My solution was to sort the questions by category and normalize the values to how they’d appear on the Jeopardy! round (e.g. $200 - $1,000). We need to sort the question to keep the relative difficult of the questions. This does not handle the Daily Double case.

There are also cases where not all questions on the board were answered on the show, which means not all question sets have five questions. I have not checked how many question sets this excludes, but for the purposes of this app, it’s fine.

At a high level, the processing pipeline looks like this:

def load() -> list[QuestionSet]:

"""Loads a cleaned up data set to use in Mesop Jeopardy game."""

data = _load_raw_data()

data = _add_raw_value(data)

data = _clean_questions(data)

question_sets = _group_into_question_sets(data)

question_sets = _sort_question_sets(question_sets)

question_sets = _normalize_values(question_sets)

return _filter_out_incomplete_question_sets(question_sets)

6.6 Trekek Bot

The final piece of the Mesop Jeopardy game is the Gemini integration. It was easy to use the API for my simple use case. I didn’t have to fiddle too much with my prompt either. It’s not perfect, but works reliably enough.

I probably should have formatted the prompt to return JSON which may have made it easier to parse.

For this prompt, I tried including the answer provide by the dataset. I did wonder if including the answer was necessary. In most cases, Gemini should be able to verify the question / response on its own.

I also worried that including the answer could confuse Gemini. The answers in the dataset are fairly terse. For example if the questions was “The first president of the United States”, then the answer would be “Washington”. I worried that maybe Gemini would be too strict and not accept answers such as “Who is George Washington?” Luckily Gemini was flexible in checking the answers as expected.

_JEOPARDY_PROMPT = """

You are the host of Jeopardy.

The current answer is {clue}

The correct question response is {question}

I respond with: {response}

Am I correct?

Start with "Yes. That is correct. " if the response is correct.

Or "No. That is incorrect. " if the response is incorrect.

Afterwards, elaborate on why.

"""

def check_answer(clue: str, answer: str, response: str) -> list[bool, str]:

"""Checks if the given answer is correct.

Args:

clue: Clue being presented

answer: The real response to the clue

response: The user's response to the clue

Returns:

bool: Whether the response to the clue was correct

answer_response: Explanation on why the user's response was right/wrong

"""

response = model.generate_content(_JEOPARDY_PROMPT.format(

clue=clue, question=answer, response=response)

).text

if response.startswith("Yes. That is correct."):

return True, response[len("Yes. That is correct."):]

return False, response[len("No. That is incorrect."):]

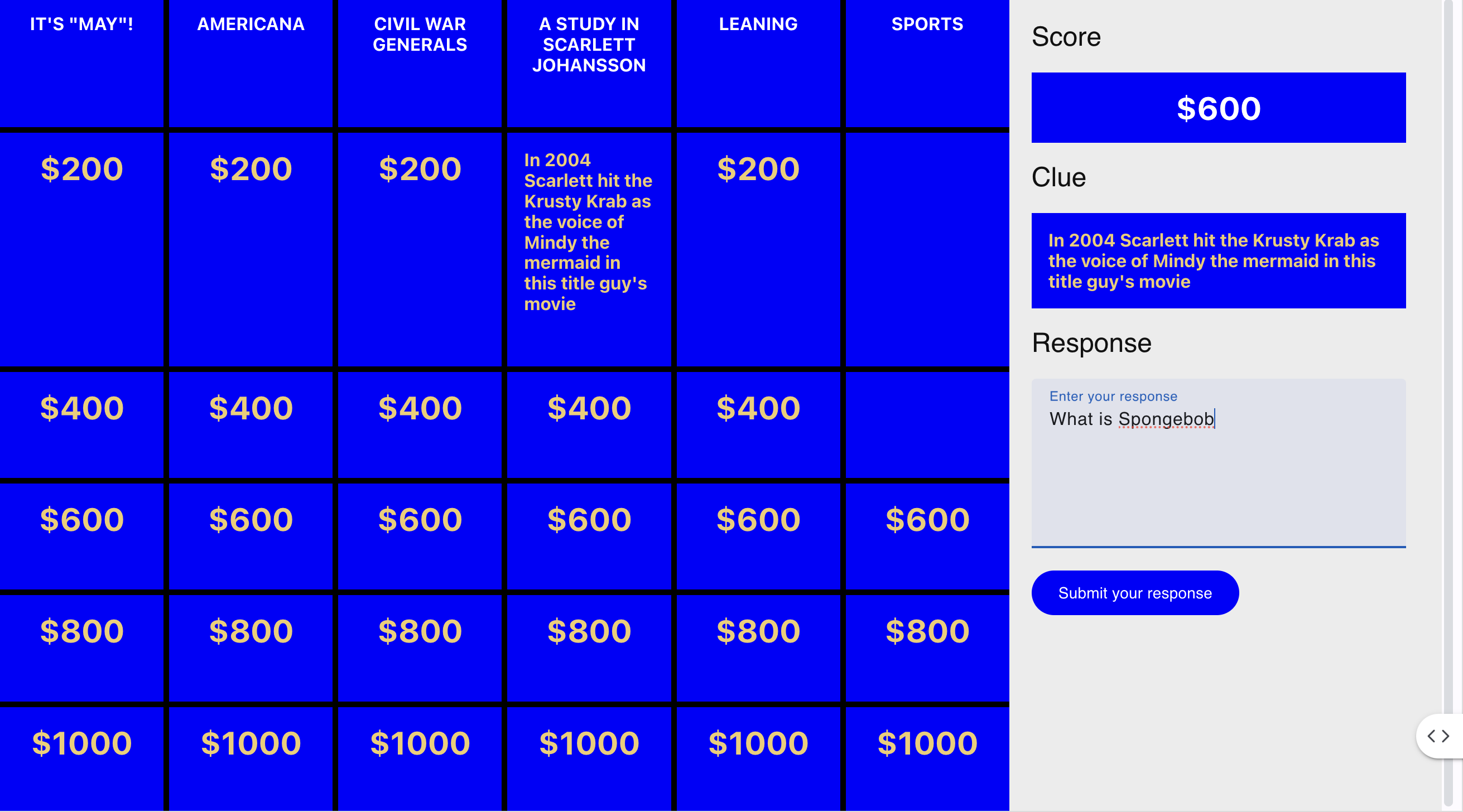

7 Screenshots

8 Repository

The code can be found here: https://github.com/richard-to/mesop-jeopardy