In my AI course this semester, one of the projects was to develop a competent AI for the game Owari. The class had a month to work on their bots and on the due date, we held a round-robin tournament. Top 2 teams received gift cards for pizza! So of course I was motivated. I can’t resist free food. And it turned out, so were some of my classmates. There were a lot of creative implementations.

Owari looks to be a simplified version of Oware, which itself is a version of Mancala. There are hundreds of variations of this game. And apparently it’s one of the oldest games in the world. Owari probably originated as a homework assignment since I found no articles on this particular version, except a homework assignment from Harvard that looks nearly identical to the one my professor handed out.

The rest of this post will describe the rules of Owari. Later posts will go into detail about my various implementation attempts.

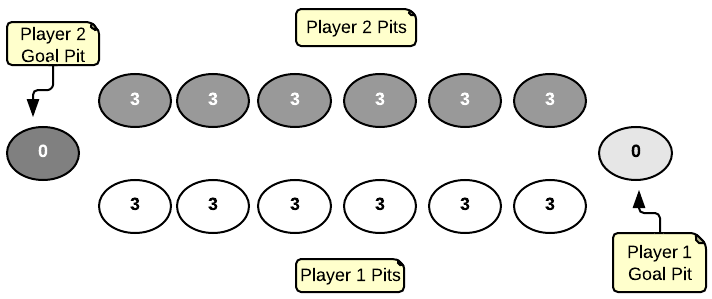

The rules of Owari are straightfoward. Here is what the starting board looks like:

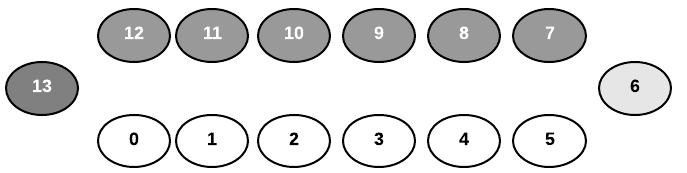

For programming the game, it is helpful to number the board from 0 to 13. This way we can store the board in an array where 0-6 represent player 1’s pits and 7-13 represents player 2’s.

Players start with three seeds in each of their six playable pits. The goal pits contain zero seeds and are not playable. Players take turns distributing their seeds with the goal of collecting the most seeds at the end of the game. The game ends when one side has no more playable pits.

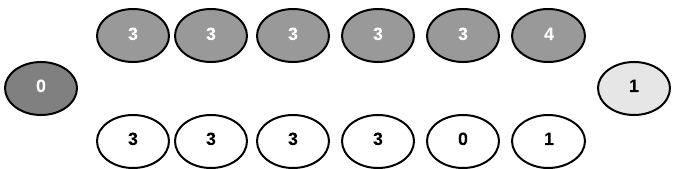

On each turn, players select one of their own pits. They cannot pick their goal pit or a pit with no seeds. Once a pit is selected, the seeds are redistributed in counter-clockwise fashion. Specifically one seed is placed in each subsequent pit until the player runs out of seeds. The only exception is the opponent’s goal pit, which is skipped.

The following image shows how seeds are distributed when player 1 selects pit 4 as his first move.

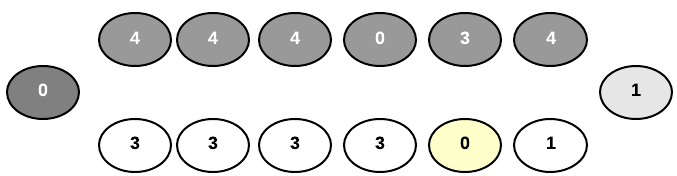

If the player’s last seed is placed in an empty pit on their side of the board, the player takes all the seeds in their opponent’s adjacent pit and places them in their goal pit.

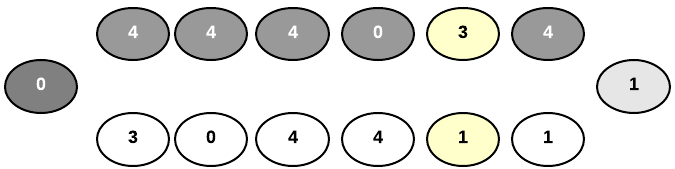

The following is an example of player 1 capturing 3 seeds from pit 8.

This is the state of the board after player 2 moves.

Player 1 now selects pit 1 since their final seed will land in pit 4. Since pit 4 is empty, player 1 can take all the seeds from player 1’s adjacent pit, which is pit 8.

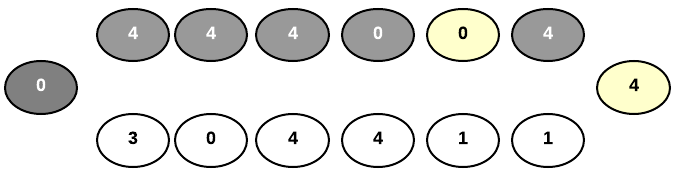

Here is what the board looks like after player 1 distributes player 2’s seeds into his goal pit.

The game ends when one player has no more seeds on their side of the board. Whoever owns the most seeds wins.